Dr Jamie Blundell

You might not expect to find fossil records in a cancer institute, but this is how Dr Jamie Blundell – an evolutionary biologist by training – describes the samples he works with.

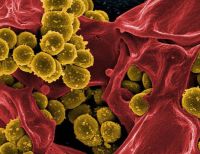

His research involves looking at blood samples taken from patients with blood cancers such as acute myeloid leukaemia (AML) many years before their diagnosis.

“If I know that someone has got cancer today, but I have this kind of ‘fossil record’ of their blood samples taken over the last 20 years or so, then I can go back to the ones taken five, 10, 15 years ago and see if I can spot the earliest signs of cancer, the signs that this person was on the road to cancer.”

Dr Jamie Blundell

Blundell uses insights from evolution and applies them to cancer, looking at how somatic mutations are acquired and expand.

“What we know about most cancers is that they're driven by the accumulation of multiple genetic changes on top of each other. What the samples enable you to do is essentially watch that process of evolution occurring, seeing how it unfolded in that person over the decades.”

To do this, Blundell takes the cancerous tissue and looks for the tell-tale genetic changes that gave rise to that cancer. He then tracks back through the older samples to see how and when the mutations arose, how they expanded and how they acquired further mutations.

Blood cancer is particularly suited to this approach, he says. “People don't come in and give you a chunk of liver or lung, but they will give you a blood sample. It's the one tissue where you can actually watch very precisely how cancer was born. And a lot of the work has pointed to the first mutations occurring very early on in your life, often in your teens.”

Blundell believes we are not far off being able to take blood samples from at-risk groups – over 50s, say – and look for genetic anomalies that suggest an individual is at a significantly higher risk of developing an aggressive blood cancer. These individuals could then be screened at regular intervals.

But detecting cancer early is only useful if something can be done it. Fortunately, there are experimental trials taking place in the US that might result in new treatments.

“This is where the detection and the treatment go hand in hand, because the very thing that you're using to detect it, which is the genetic change, will also inform your treatment. If you have a particular mutation in this gene, say IDH1 or IDH2, then there may be a targeted therapy for mutations in that gene, and so you can selectively target the premalignant condition.”